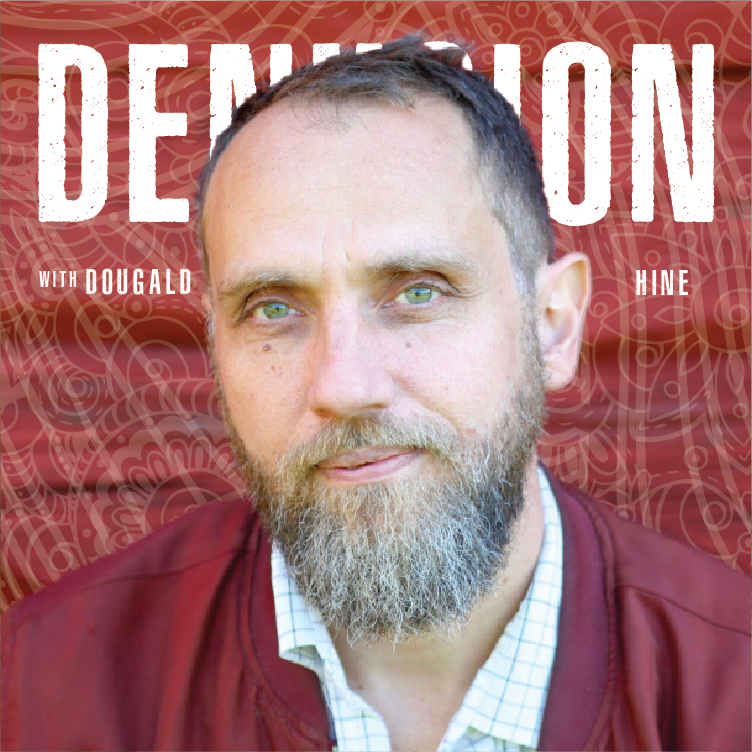

In this conversation, Dugald Hine of the Dark Mountain Project and A School Called HOME and the author of the book, At Work In The Ruins, discusses the limitations of science in addressing climate change and the need to question and reevaluate our understanding of the issue.

He emphasizes the importance of embracing vernacular knowledge and ways of knowing, as well as living in hope and embracing the home, the community. Hine also explores the need for a new narrative that goes beyond the singularization of knowledge and the supremacy of science. He discusses the concept of coming home and the work of regrowing a living culture, as well as the role of hospitality and conviviality in creating a sense of home.

Overall, the conversation highlights the importance of turning inward and embracing home as a way to navigate the challenges of climate change and create a more sustainable future.

Takeaways

- Climate change raises questions that go beyond what science can answer, necessitating a reevaluation of our understanding of the issue.

- The singularization of knowledge and the supremacy of science limit our ability to address climate change effectively.

- Embracing vernacular knowledge and ways of knowing, as well as living in hope and embracing depth education, can provide alternative paths forward.

- Creating a sense of home and regrowing a living culture are essential for navigating the challenges of climate change and creating a sustainable future.

- Hope is not a fixed concept but rather an empty palm into which something might land.

- Embracing uncertainty and letting go of the need to know the future is essential.

- Taking responsibility for the present and future is crucial in addressing global challenges.

- Getting implicated and actively engaging with the realities and needs of the world can lead to meaningful action.

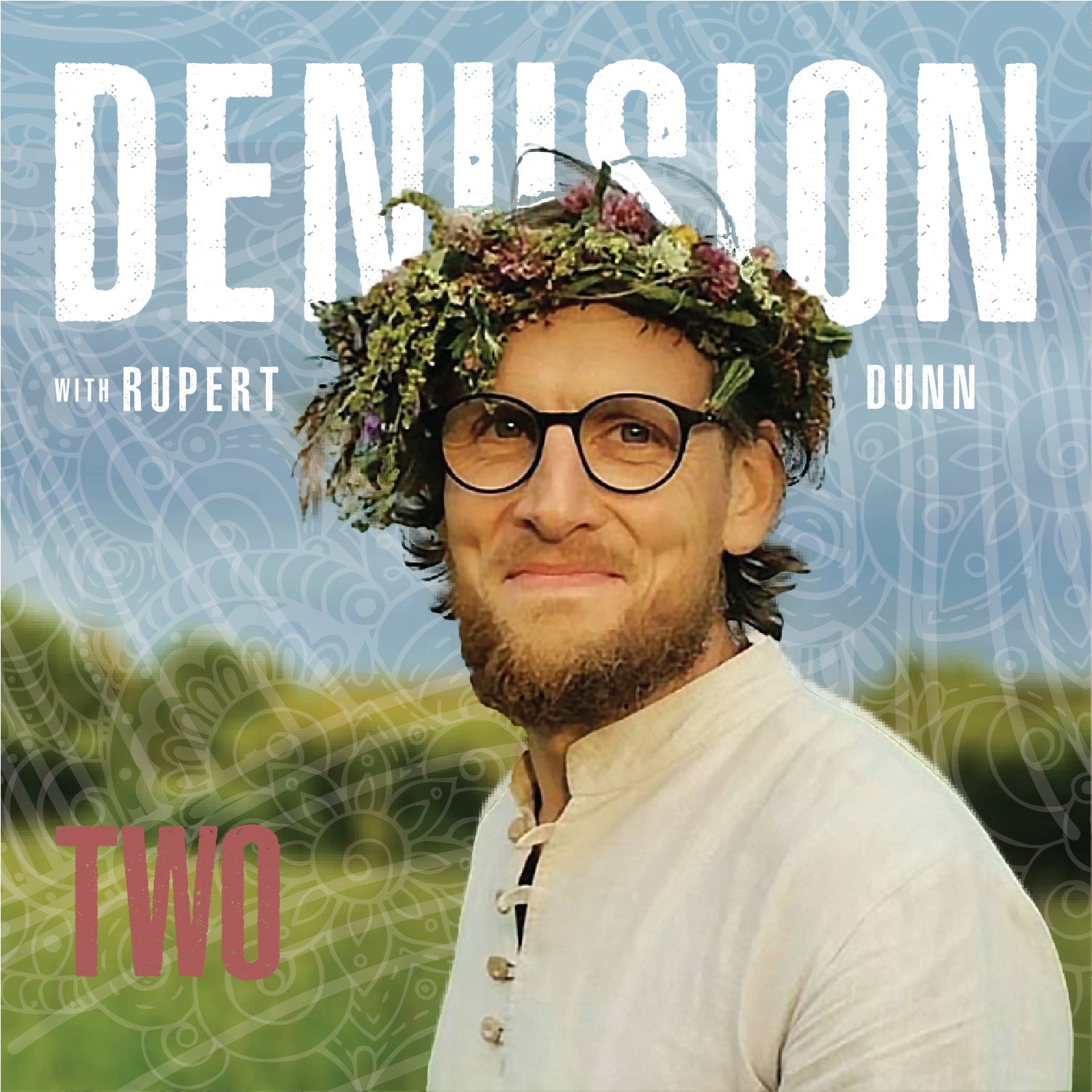

Dougald Hine is a social thinker, writer and speaker. After an early career as a BBC journalist, he cofounded organizations including the Dark Mountain Project and a school called HOME. He has collaborated with scientists, artists and activists, serving as a leader of artistic development at Riksteatern (Sweden’s national theatre) and as an associate of the Centre for Environment and Development Studies at Uppsala University. At Work in the Ruins concludes the work that began with Uncivilization: The Dark Mountain Manifesto (2009), co-written with Paul Kingsnorth, and is his second title with Chelsea Green, following the anthology Walking on Lava (2017).

Episode Transcript

Daniel Griffith (00:02.648)

Hello and welcome to another episode of Denusion It is 8 a.m. my time. It is 2 p.m. my guest's time. I'm getting used to talking all over the world with our conversations with Rupert in Lithuania recently. It's one glorious way to start a morning. Usually I wake up and I read and I write, watch the sunrise, go out and work the animals and such. This morning, my wife...

is handling the quote unquote chores and I get to sit inside in the library in our house talking what I think through is to be an amazing conversation. I have with us Dugald Hine He is a social thinker, writer, speaker, and the co-founder of the Dark Mountain Project and recently a school called HOME. His latest work, which I think we'll be talking at great length about I have here, it's called At Work in the Ruins. It is completely sticky noted up, completely

I really enjoyed this work. So thankful for Dugald and the publisher Chelsea Green for sending it my way. And he also writes, I want to note, on Substack under Writing Home, I believe. And so you can learn more about him there. Listen to the episode at the end. I'll give him a short space to note how you can get in contact with him. You can find him, support his work, etc. But for now, I want to get started. Dugald, thank you so much for being here. It is a true blessing.

Dougald (01:25.494)

Well, thanks, Daniel. It's good to be starting your day with you.

Daniel Griffith (01:32.557)

Yes, yes. I don't know many other better ways to start a day than to have an amazing conversation with someone of the likes of you. And so I do count it as a blessing. The one place I want to start, and then from here I really do have little notes. I have many sticky notes in the book. I'm sure you have many things that you can talk about, but I just want to see how the conversation emerges and evolves. But I want to start with this central question. You know, in the book you ask...

You really state that climate change asks us questions that climate science cannot answer. So inevitably from the get-go, we are separating the idea of climate change potentially from the science, quote unquote, the science, but we're also getting to something quite deep there. So I just want to start with that. What does that mean, that climate change asks us questions that the science, the climate science cannot answer?

Dougald (02:27.03)

Well, so the thing about climate change is it comes to us framed as a scientific concept. It's the work of the natural sciences that discloses to us this aspect of the trouble we're in. And partly because those parts of ourselves that are most kind of deeply schooled in modernity, let's say, have been taught to look to the sciences for authoritative knowledge.

It's the place where many of us who have been through these systems of education are most open to allowing ourselves to feel the depth of the trouble that the world is in. And there's no shortage of sense of urgency when we begin to register what the science is telling us about climate change. But the danger is, and I say this as someone who's spent a lot of time with climate scientists in different configurations,

The danger is that we have, we move straight from what the science tells us to the sort of applied sciences, the engineering and then the economics and the policy making and so on to come up with a bunch of solutions without noticing these other questions that are always implicit but that don't get spelled out clearly if we are talking as if the science can do all of the work of knowing a thing like climate change.

telling us about the trouble we're in and what it calls for. And the example that I use in the book is I say, how did we find ourselves here? Are we here as a consequence of a piece of bad luck with the atmospheric chemistry, that it turned out, whatever it was, seven generations onwards from the point where...

we committed to this path of industrial modernization based on fossil fuels, that the carbon emissions and the rest of it being thrown off by burning those fuels was sending the climate system within which humanity has inhabited and got to know and created the kind of world we were born into over the last 10,000 years. Is it a piece of bad luck with the atmospheric chemistry? Or is it a consequence

Dougald (04:48.718)

of a way of approaching the world, a way of seeing and treating everything and everyone that would always have brought us to this kind of trouble, even if the atmospheric chemistry were different, even if the IPCC would turn around tomorrow and go, guys, terribly embarrassing. Turns out we got our sums wrong. You can release as much CO2 as you want. They're not going to do that. But we have these two very different ways of answering the question of how did we find ourselves here.

Is it just bad luck with the chemistry? Or is it a consequence of a way of inhabiting the world, a way of engaging with everyone and everything? And depending on which way you answer that, what's called for next looks very different. Because if it's just bad luck with the chemistry, then what's called for next is technical hacks and tricks and fixes to try and keep things as much as possible on the trajectory that they were on, but whilst taking out the carbon emissions from it. Which...

is basically how the mainstream response to climate change has gone, with limited success, frankly, but that's been the approach, that's been what we are asking for. Whereas if it's about how we're approaching the world, how we're seeing and treating everyone and everything, then that existing trajectory is part of the problem and would be even if you took the carbon emissions out of it. And the danger that I began to see

was that the authority of this thing called the science is such that the questions don't even get asked. And so you end up on the default path, which is the one that doesn't question the existing trajectory. And not only that, but the scariness and the urgency, which is all real enough around climate change, causes us to double down on the green version of that default path of...

techno fixes and hacks and the rest of it, and feel like we're in much too much of a hurry to step back and ask these larger questions. So that's really, that's what I'm saying when I say, it asks us questions that the science can't even recognize clearly. Like they require other skills, they require other ways of knowing and being to be brought to the table for those questions to be even caught sight of clearly.

Daniel Griffith (07:08.08)

Thanks for watching!

Yeah, is this a lapse of scientific ability or do you think this is a lapse of our understanding of the right place that science has in our world?

Dougald (07:22.698)

Well, I don't think it's something that can be fixed by doing the science better. And I think that can be one of the, one of the traps when people have an intuition, the, there's something lacking in what science is telling us. Um, it can be like, what we need to do is do the science again and do it better. You know, do it more courageously or whatever. And actually I have a whole section of the book, which is called asking too much of science, because I think what we're dealing with here.

is part of a pattern that's been a recurring one for centuries within the trajectories of Western modernity, which is of asking science to do more than it can, to carry more weight than it can, to do more than actually plenty of scientists are comfortable offering to do. But we get into deep waters quite quickly when we start unpicking this, when we start asking about this, because

We're dealing with the entanglement between scientific ways of knowing and practices and the kind of strong central ideological claims and projects of modernity. And one of the things that began to dawn on me over the years hanging out with climate scientists was a lot of the people I was meeting had this slight sense of horror.

in the background of what they were saying. And it wasn't just horror about what they were learning or what their models were suggesting about where we're headed. It was also a horror at the gap between what they felt that they had been told and what was happening in practice about the relationship between the authority of scientific knowledge and the decision-making, the politics, and the rest of it. Because the IPCC was set up in the late 80s, early 90s

mechanism that would take the fruits of scientific work on climate change and turn it into political action. And, you know, a lot of these scientists were feeling, perhaps naively, we might say, but like they'd kept their end of the deal and then to their horror, it wasn't being translated into the action that was implicit in the mechanisms that they'd been part of creating. And so...

Dougald (09:43.266)

There's an element of like the curtain comes down and we see what's hidden behind the rhetoric of the way that science has figured in our stories of progress and the rest of it. And we discover, as I say, in the book that when science is actually calling into question the viability.

of the trajectories of modernity and economic development and progress and so on. Suddenly the scientists find that the authority they were meant to have is worth not much more than the voices of the protesters who are outside the gates of the COP meeting.

Daniel Griffith (10:23.932)

Right, right. That's very interesting. Because I think, you know, when I was reading the book and I think, you know, maybe I'm not alone in this, you know, when I'm thinking about these questions, you know, I'm often curious, I find myself, I should say curious onto what these questions really are. Because, you know, we are so lulled as modern people, especially in the West, which, you know, living in the United States, I can finally occupy myself within.

especially in the West, we are so overwhelmed and overcome with the science, which I think your book so delicately and completely gets into, how the science has singularized all of this, instead of the biologists and the geologists and everyone else just being inocular into the world around us, which I think science and inquisition, it's all very important. And obviously you're not standing here saying that science as a discipline is a negative or immoral force.

but rather the supremacy and singularity of the science, right, governing the narrative and answering and asking all of the questions could be the problem as you get into. Well, my question is, you know, what are some of these questions, just to really ground the conversation into some sense of reality for our listeners, what are some of the questions that science is trying to answer that maybe, you know, really needs to be answered or at least questioned more introspectively?

you know, within different communities, localities, etc.

Dougald (11:44.866)

Hmm.

I guess, really, they're questions about, where are we? Where do we find ourselves? What do we know about where we find ourselves and how we got here and what's worth doing starting from here? And I think that those questions can be asked and can be spoken to in very different keys.

Like they can be an opening onto a kind of deep questioning and allowing ourselves and our ways of living and the identities that we've acquired to be called into question. And for a long time, the reason why I was giving significant part of my time and devoting a significant part of my work to these conversations that start from people being shaken by...

an encounter with the news that scientists are bringing us about the depth of the trouble we're in when it comes to climate is precisely because that's the point where people who are in other ways very insulated against the shadow side, the consequences on the other end of the supply chains and the rest of it of modernity and the things that get packaged together into the cheap story of.

the easy story of progress. The people who are most sheltered from the shadow side of that, climate change is the point where we get shaken up and get to the place of going, oh, right, it might not be possible to just patch things up and carry on this trajectory. We might be in deeper waters than that. We might be needing to abandon the ship that we've been...

Dougald (13:43.27)

sailing on or told ourselves we were sailing on over the last few centuries and figure out what you can do then. And the moment of trouble for me that led to writing this book was part way through the pandemic, just realising that what was anyway already there if you looked at the climate movements of the end of the last decade and had placards that said unite behind the science. So

doubling down on the authority of this thing called the science rather than recognizing that it you know the work of scientists brings important stuff to the table, but we need this larger conversation of being broken open in order to even fully absorb the implications of what the scientists are bringing to our Uh to the table to our conversations, but there was a new intensification of this kind of

The science as the ultimate authority that was part of the way in which politicians were dealing with this suddenly being thrown into the pandemic and how you know, deeply alarming and unsettling that was in its early weeks and months, especially and how, you know, as politicians to say, well, we're following the science was a way of kind of dealing with this sudden pitch outside of

ordinary reality into this other timeline, if you like. But that then gets, you then get even more intensely into this thing of there being one side politically who are the people who believe in the science without even recognising that there might be a category error going on once science has been turned into an object of belief. And on the other side, people who are totally antagonised, totally alienated from that.

and those understandable feelings of alienation being also played by actors who have their own vested interests, not least when it comes to minimizing anything changing when it comes to climate. But the possibility of climate as the place that is the rupture, the fracturing of the smooth surface of

Dougald (16:09.118)

We can fix this, we can patch it up, we can make it work, we can still believe in some version of the Hans Rosling story of progress. It got more difficult, certainly for a while during the intensity of the pandemic, and I think we're still living with the consequences of that, to imagine having a conversation that starts with something that's a scientific concept in the way that climate change is, but that moves out beyond the limits of the part of the story that the scientists are able to.

to tell for us. And so that's my invitation. And by the end of the book, I have this sort of, imagine this scene of this set of conversations going on somewhere off to the side of the big path, which is the default attempt to get to the future and to continue securing the promises and trajectories of modernity, where a whole bunch of us, some of whom are and some of whom aren't professionally scientists,

are sitting around talking about, well, what's, you know, how do we know the world? What is worth doing starting from here that has some clues, I hope, for how we walk together into the unknown world that lies ahead once we stop pretending that there's this kind of big highway that's going to go on leading to the future in the way that things have been built around in recent, in the recent past.

Daniel Griffith (17:39.52)

I recently had a conversation, a podcast, which aired this past week, at this recording at least, with Rob Lewis, who I think you're familiar with, maybe even connected to, out in Seattle, Washington. We were talking about the climate change saving the world mythos that is so popular and prevalent in our own dialects. He paused and this is what...

Dougald (17:50.082)

Yes.

Daniel Griffith (18:05.412)

turning point really in my understanding of this narrative. I got the same conclusion from your book, but he paused and he said, Daniel, saving the world, we have to decide which world we want to save. Because if it's this hyper industrialistic and scientifically infused, that is to say controlled world, full of capitalism and colonialism and everything else, okay, but we have to make that decision because the world isn't singular.

Right? And science doesn't have its way as a master over that world. There's so much more at play. And I loved that. It was a healthy realization that as we look to the future, and as you write in the book, there's two roads, you know, two paths, one of them, the large way is this way that you speak about here in this conversation. You know, we have to decide what are we trying to do? You know, what world are we trying to save to some degree? And are we really even the ones that should be looking to save the world? That's a different question.

Just all interesting connections here in these conversations. I wanted to bring up John Ralston Saul, was an author back in the 80s and 90s. He wrote a number of what I believe to be really good books. One of them is called Voltaire's Bastards. I don't know if you've read it, but it's 800 page. It's a healthy read. It's a massive work of non-fiction. But in it, he postulates that it's really looking at the age of progressivism.

coming out of the Enlightenment that we live as humanity, we've emerged as humanity out of the state of nature, that's Hobbes, Rousseau, Locke, et cetera, and it created the states of civil society to cause for the ills and pains of the state of nature where every man is his own king or master or god, et cetera. And we give rights away to the state of civil society so that we are protected and we have property, et cetera. And this linear progression extends into the state of modern science, he writes.

where when the science becomes president, it presides over the operations of the world, it controls the narrative by controlling the vernacular. And that's what the rest of the book is about. How when the science becomes president, master over the world, it controls the vernacular. And I wonder if, you know, the science, and I didn't really want to probe your mind for this. I don't know where the conversation goes from here.

Daniel Griffith (20:25.696)

You know, I just, I wonder how much of the rise and singularity, the escalation of science into the four of human happenings, um, as a path director has to do with a singularization of our language, our vernacular. Um, you know, that is to say, uh, you know, if you're not an agronomist, right, a scientist of the soil and botany and such.

that you really don't understand the relationship between plants, the soil and the sun, or plants, the soil and the sun and humanity. So if you're not a scientist, you can't speak the language, and if you can't speak the language, you don't have opinions. And what I get from you, and this is the question, I get the opposite fact, that when we allow other modalities, our mythos, our stories, our local cultures, our religions, our spirituality, our communities, whatever that may be, to be the one that is speaking,

you know, really trying to understand, you know, how do we get in this? What world are we trying to save? What is the world, et cetera? When we ask these deeper questions, it seems like an uncontrollable narrative, the opposite of what Ralston Saul is talking about. I wonder, is that akin to what you're saying, or is that more of a parallel trajectory of these thoughts?

Dougald (21:45.438)

It's a very interesting set of threads to bring into the conversation. I mean, I don't know that particular book by John Ralston Saul, but that word, the vernacular, is one that resonates very deeply for me, because one of the thinkers who lies behind a lot of the work that I'm doing is Ivan Illich, who, as you may know, spoke and wrote a lot about the vernacular.

Daniel Griffith (22:08.402)

Mm. Heh heh.

Dougald (22:14.158)

And in particular, that thing that you're saying there from Ralston Saul of the relationship between science and the vernacular comes out in the work of one of Illich's friends, Uwe Perxson, a German sociologist who wrote a book called Plastic Words about 30 or so years ago, where what he was talking about was these new words that enter everyday speech. They're not...

They're not vernacular exactly, although like all language, they have their roots in the vernacular because that's the only place that words ever actually come from. But they've been taken up into scientific usage and they played limited, specific, helpful roles within the language of professional science. But then they travel from there into everyday speech and they acquire these kind of

vastly larger and more powerful resonances without having a clear definition. And what Perkson is saying is, like you end up with this kind of jargon laden conversation in which you have maybe 50 words which occupy a huge amount of ideological weight without people have to sort of gesture vaguely in the direction of experts who they think

understand fully what they're talking about, but they carry an authority that comes from that. And again, what I would be wanting to say with this is that even the work of scientists is not well served by this kind of weight and electrification of certain language and certain kinds of knowing. And maybe to go back in through your example of the agronomist, maybe what this is about

root is which kinds of knowledge we even notice are knowledge. And I think about the Irish philosopher, his name is going to come back to me in a moment. He's John somebody, but he grew up in rural Ireland in the early 20th century. And I heard him say in a recording of an interview with him, you know, when I was growing up,

Dougald (24:37.854)

if everybody over the age of 14 had just vanished overnight from our villages. Those of us who had left would have been able to run the farms and the villages. All of that knowledge was already part of what was bred into you through a rural upbringing in rural Ireland or many, many other parts of the world until very recently. And.

Daniel Griffith (24:55.984)

Mm.

Dougald (25:05.138)

Those were communities which from the perspective of the education system, which this guy then was taken up into and prospered for a while within, were considered to have no knowledge. They were ignorant, backwards, uneducated people. And meanwhile, I was reading a piece just the other day from Debbie Casper, who's a

an American academic who's a member of our community around our school, who she was writing about this very humbling experience of the first cow coming to the little farmstead on the edge of the college that she's been involved in setting up over the last year or two. And just her, you know, being really kind of brought down to earth and brought down to the cow shit by the experience of this animal that she's taking responsibility for.

arriving and discovering all of the things that she ought to have thought about and that she hadn't. And I just, I found it particularly potent that she was telling that story in the context of this little farmstead being set up on the edge of, you know, a liberal arts college in the United States, because it's precisely these different kinds of knowledge. It's the high status knowledge of the person with the PhD in the institution that's organized.

Dougald (26:29.218)

that's being shown its own helplessness, its own cluelessness before the kind of peasant knowledge of how to look after an animal and be part of the systems of life out of which in one way or another most of us are fed. Those kinds of encounters and the ruptures that they produce, that to me is where it gets really interesting.

And it's striking to me in Hospicing Modernity, the book that Vanessa wrote, which I draw on quite a bit in my book, she talks about education for mastery. And then against this, she sets education for depth or depth education. And that's a language that I can used with her for a few years. But actually Debbie Casper's story of this moment with the cow made me realize that the simplest sense of depth education is

Daniel Griffith (27:03.567)

Yeah.

Dougald (27:24.974)

that it's on the same axis and pulls in the same direction as humbling, being brought down to earth, being shown the gap between your high-flown ideas of who you might be and what you're worth and where your credentials are, and the kind of having to deal with soil. And it's getting back into that. It's getting back into those kinds of relations and those ways of knowing and not disparaging the parts that

are held by and brought by the work of science to that, but not elevating them either above the knowledge that is embedded and embodied within communities that are living in place and groups of people who are willing to roll with the foolishness of coming in adult life, having been groomed for some more high status position to get in and muck in the buyer. To me, that's the.

Daniel Griffith (28:09.968)

the foolishness of coming in adult life, having been groomed for some more high position to get in and not in the bias. Do you think that's where the pull is? That's where it gets, that's where it gets me? Yeah, I don't have this page earmarked, but I have it in my recent memory, and so maybe you can draw this quote further for me. It's in your book. It's a quote from Martin Prechtel, or Martin Prechtel, and he talks about how, you know, there's a certain group of people

Dougald (28:21.739)

That's where the pull is. That's where it gets interesting.

Daniel Griffith (28:39.884)

And again, you can clarify this for us. There's a certain group of people that it's surprising to him that wake up believing that like life is theirs that day or that they're not going to die that day or whatever. And you go into a couple page analysis of this and there's a huge connection I think between what you're saying there and what you're saying here. So could you dive into that for us?

Dougald (28:59.318)

Yeah, sure. So this is, it's a story that Stephen Jenkinson tells about Martin Preckdell. And he says, yeah, Martin was teaching this time and we were all sat there. And I don't know, but I imagine it's a group of mostly white North American folks who are sat there. And then there's Martin, who's got this kind of complex and fascinating kind of indigenous background and life experience and so on. And he sat there and he says, hmm, it's really strange where...

where you people come from.

Where you come from seems like everyone wakes up each day expecting to live. And, and Stephen has a whole beautiful commentary on this where he's kind of wondering about what the alternative to waking up expecting to live might be. And he's like, it's so easy for us to hear that and to have been sort of groomed into a way of thinking where we go, the alternative is that you're waking up expecting to die.

that you're kind of living under such terrible conditions, that the realities of disease and infant mortality and the rest of it around you are so awful that you don't have this blessing that we have that we get to wake up expecting to live. And he's like, I don't think that's what Martin is talking about. I think it's more like that if you don't just wake up with that as an expectation, then maybe you can start each day being grateful for another day.

And that to me, that taps straight down into Illich as well. Illich would again and again contrast the stance of hope and the stance of expectation. That expectation is that sense of entitlement to a system that will deliver my rights and.

Dougald (30:55.054)

to a future that is a predictable extension from the present and that can be controlled and managed. Hope is living open to surprise, living open to the unexpected agency of others. It's not pretending that I know the end of the story just because I have a well-founded sense of the depth of the trouble that we're in. And...

I think that until very recently, the only way that people made life work was by living in hope. As I say near the end of the book, there are plenty of achievements of modernity that we would not gladly surrender. But in order to have the best chance of bringing the achievements that are most real and most to be cherished with us into the kinds of future that we're likely to be heading in, we have to get out of the mentality of it all as one.

bundle that is progress, none of which can be surrendered, and into a reckoning with the things that got lost along the way that need to be woven back into the story, the parts of what we've told ourselves was so amazing that actually were never as good as we told each other they were. And it's through that kind of humbler reckoning with what we try to take with us, what we mourn, what we recognise we're being given a chance to leave behind.

And what are the threads from earlier in the story that we're being given a chance to pick up and weave back in, that we find these kinds of onward paths beyond the failure of the promises of modernity, beyond the attempt to cling to this idea of the kind of big path that's an onwards and upwards singular converging trajectory. And I don't know that there's any way to do that without learning to live in hope in that Illichian sense.

that is a hope that's grounded in surrender, that's grounded in not knowing the end of the story, rather than a hope in the kind of false optimism sense that is so often where we've been taught to look for something called hope in the societies that many of us grew up in.

Daniel Griffith (33:11.08)

Yeah, it seems like this, these converging crises that you write about from climate change to the pandemics, etc. You know, they really differ, you know, our responses, or the viability of our responses in the actual world of things, that is to say the viability in the actual world of things in our responses really differ or diverge in the stories that we tell ourselves. Really the stories that surround us, of course, that's the central mythos. To me, the scientific mythos or mythology.

is that knowing to some degree is power. And the more we can possibly know in some sort of disconnected sense, right? That when a plant grows, it undergoes photosynthesis. And if we can only just understand a plant's photosynthetic process is good enough that we can increase it, we can maximize it, we can harness it, et cetera. And Rob Lewis in that episode a couple days ago.

You know, he says it so powerfully that the word nature and environment, while we use them interchangeably today, are two entirely separate words. He says that nature is a word with dirt still on its roots. I think as if I can paraphrase, maybe it's a close quote, but nature is a word with dirt still on its roots. Whereas the environment, which, you know, really necessitates that we say the environment, we have to separate ourselves from it and call it some other entity that isn't

You know, everything that is all around us, the air, the thermal radiation, the breath, everything else, the love, the community, the vigor, the vitality. You know, the environment as we become separated, we can use this term to talk about resources and extractions, right? Environmental services, you know, climate, climate smart farming is for the maximization or optimization of environmental resources that we can continue to work with or maximize or extract for.

you know, to solve climate change or to live better lives or to grow civilization or whatever the end might be. But I'm getting that it's a story, right? It's the stories that we tell ourselves. And when we trust the science, we are in some sense trusting our lives, which are living stories themselves, over to that singular story of science. That knowing to some degree is grounding in this reality. That if we only understand, though, the way in which the temperatures are rising,

Daniel Griffith (35:28.528)

that we've become grounded in the fact that we can now address that one singular thing to produce an outcome. But as we decentralize that story, as you bring it more towards our home, our communities, the localities, et cetera, and we start to look at life from a non-reductionist, non-totalitarian, the scientific type perspective, to me, it seems like that story becomes simultaneously ungrounding in the ways in which we have been grounded.

but also grounding in the ways which we have long been separated from, ancestral traditions, indigenous worldviews, and world truths, etc. And so the question here is, I mean, one, we can address what I said, maybe I'm incorrect in some of my thoughts, but two, what is this new story that we have to inhabit? Because climate change, as you write, it's very real, right? The world is increasing the, I mean...

the heat, I mean, we can go on for do a whole podcast about the ecological realities of climate change. So if we accept that as a foundational assumption that the climate is changing and this is somehow in some degree negative to human civilization, what is the stories that we have to start looking at and telling ourselves and imbuing in our own lives to really go down that separate path?

to start walking down that new way, which I think is simultaneously very old way.

Dougald (36:53.934)

So I always feel a touch of caution when we start talking, as though what we're looking for is a new story. But equally in the way that I described this kind of fork in the road in the book, on the one side, what you've got is something that is at least claiming to be this kind of super highway on which lots of things are converging. And on the other side, what you have is a kind of branching of paths that are made by walking. And so maybe in the same sense, it's kind of branching of stories.

that we're looking for, but I think there's a clue in what you said already about the story of knowledge as power. And another thing that Vanessa underlines in Hospicing Modernity is this sense of modernity as being an episode within which being is reduced to knowing. So for something to exist, it has to...

know or it has to be known. And that has all sorts of knock-on effects. So firstly, it devalues people's existence as simply beings and says we don't matter unless we can prove that we know things and you can see the patterns of that playing out within our societies. But then it also limits what is allowed to be real to that which

we either know already or are going to know when we've got further down the path that we're on. And so the possibility that there are all sorts of aspects of the kind of world that we're in that elude human knowledge entirely, or certainly the kinds of human knowledge that science allows us to secure, however provisional good scientific work always actually is.

Those things have to come back into play, I think, in terms of where stories on the far side of this event of modernity, this episode that was modernity, this world as we've known it around here lately. So we let back in the marginalized forms of knowledge, the things that we weren't meant to take seriously if we wanted to be taken seriously.

Dougald (39:22.33)

And another piece of this is that kind of the knowledge as power as we've imagined it, I sometimes think that it's modeled on a particular way of understanding what a Christian god might be like or what it might be like to be a Christian god. That we have this idea of this sense of agency as being, like step one is omniscience. First, we have to know the world.

not for here and for now, but for once and for all, as if from above, as if from beyond, as if from outside, the satellites I view. So that's the precondition before we can get to acting is we have to secure that kind of knowledge. And then we have to act as if omnipotent. So we have to come up with plans from above and then project those down on and into the world.

And firstly, I'm not even sure theologically that that's a particularly good way of imagining what it would be like to be the kind of God that Christianity or the Abrahamic traditions are talking about in the first place. But secondly, if that's our sense of agency, there's a danger that we sort of lose faith in the possibility of those ways of knowing and acting. And then that leaves us feeling utterly ignorant and utterly lacking in agency because we haven't questioned.

that framework of what knowledge and what action would look like. And that, again, is where this kind of humbler ways of knowing and acting that involve participation rather than standing above and managing offer us ways out of the paralysis that I think can be another version of what the shadow of the shiny promises of modernity looks like, is that we can be left at this end of the story, you know, feeling

like, well, we can't make good on the promises that were once confidently made, and therefore, we don't know anything, we can't do anything. It's a sort of postmodernist kind of place to get stuck, I guess. And I think that what a lot of us have been stumbling towards is ways out of that trap, which, you know, not limited to, but do include being willing to come back into relation with.

Dougald (41:46.642)

earlier ways of knowing, earlier practices, earlier stories, not on the basis of some fantasy that we can be going back anywhere, but that they are carrying, that they continue to exist, though they've been undervalued or kind of hidden from view, but also that they're carrying more than we allowed them to be carrying while we were deeply confident in the grand stories of modernity.

Dougald (42:17.91)

listening to things that people have been trying to tell us for generations from those communities that have been on the receiving end of projects of modernization, rather than those that have seen themselves as the heroic agents at the center of the story of modernity, not least coming into relationship with listening to Indigenous voices, but also not putting all of the weight and all of the responsibility out there onto...

people who we can easily imagine and project onto as the others, but recognising that within our own lineages and ancestries and places and cultures, there, along with all of the shit that needs composting, there's also stuff that was what kept our ancestors going, that has, you know, has gifts for us.

in ways that can be more challenging for us to engage with, perhaps, than to just put it all onto going and learning from the indigenous folks and projecting some idea of timeless wisdom onto them, rather than recognising that we've all been living in a state of culture, in a state of experience, rather than innocence, for a very long time. And it's precisely the

the fruit of experience, the fruit of knowing, including knowing the costs that we've been outsourcing for recent generations that leads us to the place where we might have something that's worth the name of wisdom.

Daniel Griffith (44:02.777)

Yeah, let's utilize this I think as a springboard. I want to talk about a school called home because both your substack writing home and a school called home to me are very connected. But as I understand it, and please, please correct me, it is this coming home, right? And you know, not to a house, not to a particular, you know, version of a hearth, but the idea of coming home to ourselves, which is what I think you're getting into there.

you know, with this understanding of, you know, we all have this ancestral legacy of our ancestors really inhabiting and, and co-creating in place for long epochs and periods of time. And that truth is still within us as it is within, you know, modern wisdom holders and indigenous peoples. What is the work writing at home or writing home, excuse me, your sub stack or a school called home? What does that work look like? But also how does it really come into conversation with

the conversation and the dialogue we've been having for the past 45 minutes on, you know, being at work in the ruins. How did these two stories converge?

Dougald (45:02.966)

Well, somehow we have to find ways of making home in exile. We're not about to go back to some primal home or some romanticized version of how life was before it all went wrong. But precisely because life has been harder for most of our ancestors most of the time than it has been for most of us around here lately in some important ways.

there is practical knowledge, there are ways of making life work that are the only thing that got our ancestors through that we've been able to neglect in recent times around here. And so for me, this language of home, you know, it partly is this kind of humbling thing of, you know,

the point at which you get over your ambitious, heroic idea of going out and fixing everything, changing everything, putting everything right or whatever, and realize that the hard work might actually be at a humbler level. It might start from gathering people around the kitchen table. It might start from being a good neighbor. It might start from...

getting involved with where your food comes from, and that this takes you into relationship with the ways in which people have lived in other times and places, including your own ancestors. And it takes you into, you know, the thing of the vernacular, not just in the sense of language, but in the sense of practices, because the vernacular literally means the homemade, the homebrewed, the home-spun.

And that's why Illich is kind of gesturing towards it. And so part of how I found my way to this language of home and part of how Anna and I ended up creating a school called home was from that thread from Illich and his writing about the vernacular. Part of it comes from John Berger, who's another thinker who's been very important to me and who absolutely embodies, you know, in his mid forties when he was, I guess, about the same age I am now.

Dougald (47:19.094)

having grown up in London and been this sort of international Marxist intellectual and art writer and so on, he ends up settling in this village in the Haute Savoir in France with the last generation of peasants and he says, you know, peasants don't find it very easy to trust you as an outsider, but what allowed me to arrive here and he ended up, you know, spending another four or five decades there, the rest of his life, living in that village. He said part of what allowed me to find my way in and

be in place and learn from the people here was my willingness to make a fool of myself by being a grown man who didn't know how to do any of this stuff but was prepared to muck in anyway and we got to laugh together and in that barriers came down and I became this kind of rather aged apprentice to these old peasants. And he talks about home and he borrows strangely from the scholar of

comparative religion, Messiah Eliade and Berger, who's coming from a very different place politically to Eliade, but says, Eliade has this nice definition of home being the crossing of two lines. It's where the vertical line, the line that connects us to ancestors, that connects us to gods, that runs backwards and forwards through time, meets the line that runs through space, the line that runs out across all of those who I share this time with.

the journeys I make out into the world, and I return. And if I have a place to return to, then that place is home. And if I go out into the world and I have to dwell somewhere, then I have to have the practices. And Burgess literally looking at migrant workers living in hostels in Europe in the early 70s when he's thinking and writing about this. And he's noticing these tiny practices of homemaking by which people keep their bearings under very harsh.

conditions separated from their places, separated from their families, these little rituals by which that connection in the vertical and in the horizontal is reenacted and is part of the mechanism of survival and of holding meaning under very difficult circumstances. So all of that is there in the mix of how home came to be so resonant for me in the language of what I'm writing and

Dougald (49:40.202)

in what Anna and I are doing. But the other part of the story is that, from when Anna and I first met.

One of the things we came together around was a shared sense, a deep sense of the importance of hospitality and conviviality, and that these weren't just things we liked, but things that mattered very deeply in ways that were hard to express in modern, respectable intellectual language, but that actually are close to the heart of how human beings live together, live well, make lives worth living.

And from early on, we knew that sooner or later, we were gonna want to create some kind of gathering place that built on the work that both of us had done in our lives so far. And we were having this one conversation where Anna was like, whatever it is, it's not an institution, it's not a center, it's not an institute, it's none of those things, it's our home. And it starts from and returns to that. And so we always say,

this school is, it's a school called Home. It's a school that starts from and returns to the conversations we bring together around our kitchen table. And it's a gathering place for those who are drawn to the work of regrowing a living culture. And some of that's very international. We'll have 20 different countries represented on a call in one of our online series. And some of that's very much.

a local in this town of 1,500 people in central Sweden, where we found ourselves making a home and making a life and welcoming people into this space that used to be the shoe shop here in Astervala. So those are some of the things that this kind of centering of home means in practice for me and for us.

Daniel Griffith (51:36.328)

Yeah, I think that's unbelievable. I think a lot of us, when we hear this idea that you're pushing forward so eloquently, about not a mistrusting of science, but a replacing of where science should be, right? And maybe itself wants to be as an ocular into the world around us, just like experience and ancestral wisdom and everything else is an ocular into the world around us. And it gets us into being and relationship, etc.

And as it ascends, it becomes less in its ability to do these most wonderful things. You know, I think we hear this and we think that, you know, that the opposite end of this is the opposite result would be isolation, you know, a reducing of our ability to live in this world, et cetera. And what I'm hearing from you, especially in this last little bit is it's really the opposite, that when you turn in that inward turn to home, imbues light elsewhere.

like 20 different countries being on these calls, all habitating together, really trying to understand what this idea of home is, let alone just in your own community. We live, my wife and I, Morgan and I, we live in the middle of nowhere, central Virginia here. There's 109 of us that live in the city, most of which are very old and ancient. And in a very similar but entirely dissimilar way to what you're describing in the French peasant villages, that was one of the realizations we had when we first moved here. It's an entirely different form of life.

that we were not ready for. We moved here eight some years ago, and we had our first child, Ellewyn is her name, and she was born here on the farm, et cetera. And we looked at our neighbors who had been here for generations. And we asked, well, is she a native Virginian now? Is she from Ohio where we came from, the Midwest of the United States, or is she Virginian? And he said, unless your great grandfather is buried in your yard, you really can't claim Virginian status.

And I think that same idea is painfully, but entirely made even more true when you look at the ancestral indigenous lineages and legacies of these places, right? That they really truly inhabit Earth. We have to be here. We have to care. We have to turn towards home and find life there that we can't, you know, just go out, determine the science and just, you know, go start spreading our arms everywhere and simultaneously still be grounded.

Daniel Griffith (54:00.788)

And so I say those things, I don't know if you have anything else on your docket that you want to get through. But that to me is hope. You know, this idea of home that it's still possible. Because as you write in work in the ruins, you know, with climate dysphoria and depression and everything else, I mean, entire generations right now are being raised and reared. You know, as they're told that there really is no future.

That life as they know it is not going to exist in the world. And there's truly, you know, I was reading these statistics that came from 2018, which is really important. Um, really it's, it's pre COVID, you know, pre a lot of this industrial collapse, pre Ukrainian war, you know, Israeli Palestine, Palestinian conflict. And when they have, there's a, it's pretty, a lot of this pain that we've experienced globally as a people over the last four or five years. And it was that, um, I think it was 17%.

of teenagers, I think it was 17% of teenagers today have considered suicide, 4% have attempted suicide and nearly 70% of those attempted suicides have resulted in hospitalizations. It was very successful, not completely successful, the suicide attempt, but it was so successful, the attempt was so strong and sure that they required medical attention to stay alive.

You know, and I think about these things, you know, and you think about science cohabiting this narrative and, you know, it's something that draws me to your work. The reason I wanted to jump on a conversation with you is, you know, it's not dystopic. You're not envisioning the future of the world as its ultimate collapse, you know, and this pain and war and pestilence and everything else. In fact, your book truly ends with saying that we have to be comfortable with not knowing the future, you know, as I understand it.

But there's hope there. And maybe if we could just, let's end on this notion of hope. I'm sure you want to speak to some of it. But I'll give you the floor.

Dougald (56:01.63)

Yeah, thanks, Daniel. I think it's this, it's the kind of.

the subtle, the delicate understanding of hope as, you know, not something you can hold on to or grip tight to, but as, you know, it's hope as an empty palm into which something might land, something that you might need to carry as gently as if you were carrying a young, small creature. And that the form of that, what it looks like, what it feels like,

what it means in practice is going to be so dependent on where you're starting from, where you find yourself. And, you know, the thing of arriving into a place where plenty of people around you are generations deep within the place and you're coming in as an outsider, that can be every bit as humbling as the moment where that first cow comes off the back of the truck and you realize all the things you don't know. It can be just as good a way of having

your story of yourself, your social capital and credentials and the rest of it pulled out from under you. And like you say, that can kind of, it can unground you from the things that you've been taught to treat as solid ground to stand on and call you to actually get into the ground, into the mud, into the mess. And there are no options from here that involve kind of

running for the hells and disconnecting from the trouble that we're in. The trouble is going to be there waiting for you, however far and however fast you run. But equally, there are things for you to do wherever you find yourself, whether it's in the middle of a vast city where there are huge numbers of people living in isolation, surrounded by millions of human beings.

Dougald (58:03.174)

or whether it's in a community of a few hundred or a few thousand where you as an incomer might be simultaneously an object of suspicion and of deep curiosity and a significant tipping in the scales of the viability of whether this community is still going to be there in another generation. And all of those things are into play as you start getting to know people and taking responsibility for a bit of land or whatever it is.

you find yourself with. And it's just this sense that.

None of us are going to live to see the end of this story. It's easy for us to use a language that's so saturated in urgency when it comes to climate change that it feels as if those alive now are not going to live to be old. And none of us can ever actually fully take for granted living to be old, but there is a lot more to come. There's a lot more trouble to come. There's plenty of trouble that's been here all along, but that some of us were able to separate our.

ourselves from and not recognize our implication within. What's called for now is to get implicated, to get aware of the gap between the stories we've been telling and the realities we're in, and then to look for, to listen for, to feel for what's calling to you and where the thing that makes you come alive meets the hunger and the need and the urgency.

in the place where you're starting from or the place that you're called to, rather than, you know, trying to see it all, trying to spend too much time seeing it all from above and getting paralysed by the fact that, you know, neither you nor I nor anyone listening to this is really in that God's eye perspective, and that might even not be what it's like to have the perspective that God might have on any of this either.

Daniel Griffith (01:00:03.349)

Get implicated. I love it. I love it. I think that is a fine and simple way to say it. Dugald, thank you so much for being here. I had great expectations for this conversation, only because my knowledge of you and your speaking abilities and your mind's power. But I have so enjoyed this conversation. I feel so blessed. Thank you, truly.

Dougald (01:00:24.002)

Thank you, Daniel. It's a pleasure to be together.